I saw this little boy at school one morning with tears in his eyes, asking for his daddy over and over. This was not the first time. It had started a few days ago. I found out that his father’s new job or role required him to travel, something this child was not used to. He was gone for several days at a time. It was clear that the boy was missing his father and hadn’t accepted the new arrangement.

So this particular morning, we were just starting to gather for our morning circle when he started crying again and hung his head over the low door to the classroom, looking out. I walked over to him and got down on my knees to his eye level so I could see his little face and he could see mine. I said, “I see that you are feeling sad. Hmm. Are you missing your Daddy?” He nodded. I asked gently, “Would you like to come over and sit with me at the circle?” He nodded again. So I offered my hand, he took it and we walked over to the room where we usually sit to do our opening and closing circles.

He was still sobbing a lot at this point. I repeated, “You are really missing your daddy. You know, my daddy lives a bit far away too and sometimes I miss him a lot too.” He gave me a look that sort of meant, “Oh?” through his sobs, which now seemed to be slowing down. I asked him how many days his father was gone for. He replied with both his palms up and fingers out, “10!” Before I could say anything else, he said, “But he will be back in 5 more days. It’s already been a few days since he left. 5 more! He went in a car! He went really far away!” His sobs slowing even more.

I asked him with genuine excitement, “So when your daddy comes back, what are you going to play with him?” His eyes immediately lit up. “You know, my daddy bought a toy and left it at home before he went on his trip! When he comes back we are going to open it and play with it together!” His face was all smiles now and the tears had stopped flowing. There was no more sadness in his voice. He then proceeded to describe the new toy in detail. I said, “That sounds really exciting!” He replied, “Yes! We’re going to play a lot!” I smiled in return and patted his back.

He then sat next to me with a smile and proceeded to enjoy the songs we sang as part of morning circle time. The rest of the day went quite pleasantly for him too. He didn’t cry again that day and went home with a smile. For that day, he seemed to have found his peace with his dad being away.

Being away from a loved one can be very hard. This is especially true for little ones, given, that they live a lot more in the moment and do not fully have a grasp of the concept of time. Before I became a parent, my idea of making a sad child feel better involved some combination of silly faces, pointing out to things that (I thought) would be exciting to them, singing, dancing – essentially anything that would distract them away from those feelings of sadness. Then they’d stop crying. I considered it a win – they forget about the sadness and feel better, right?

I couldn’t be more wrong. The distractions did not make that sadness go away. It suppressed the sadness for a little while, pushed it down. It eventually resurfaced, but I never looked at it that way back then. I was back into full distraction mode and voila! It went away again. In some cases, it would take many distractions to make the crying stop. And, needless to say, I never considered the effect of what I was doing on the child’s ability to handle sad feelings in the future.

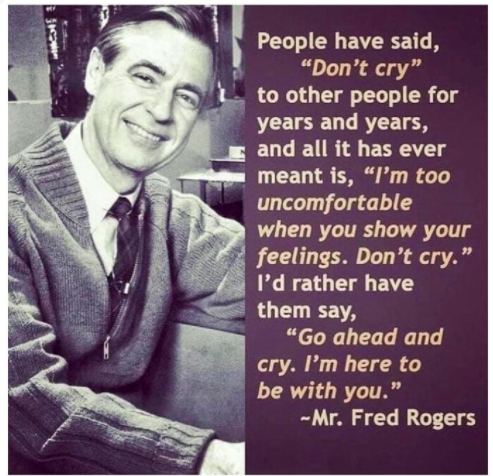

What I hadn’t realized yet, was that I was feeling uncomfortable with their big feelings and the crying. The children were not the ones feeling uncomfortable. It was me all along.

After becoming a parent, having worked as a teacher to children in a few different contexts, researching the nature of anxiety, sadness and depression (to help out a few loved ones over the years) and working through my own emotions, I have come to this important realization – that humans fundamentally crave to feel understood, to feel connected with someone, more than anything else. At a subconscious level, we want to know that it’s okay to feel what we feel, no matter how low or dark the feelings. That feeling of relief from knowing that *someone* understands you without judgment, creates a sense of connection. And genuine connection is a step towards healing.

What I realized was that trying to “cheer them up” or “make them happy” is sending the wrong message – that it is wrong to feel sad. That it is not normal or okay. That’s a lot of pressure to put on a child (or anyone, really) – they start to feel like they need to hide their sadness and perform being happy in front of us, because their sadness makes adults they trust feel uncomfortable.

Today, I approach the same situation very differently. I usually sit with a sad or crying child, acknowledging their feelings if needed, listening to why they are sad. Naming the feelings (e.g. sad, frustrated, disappointed) also gives them the emotional vocabulary for such feelings that cause discomfort in their bodies. Sometimes, I simply sit with them quietly because not every child will want to open up about what made them feel sad. Not every child reacts positively to feelings being named in the moment. That’s okay too. Mostly, I try to be the calm presence they need in that moment, without the pressure to “stop crying” or “don’t feel sad”. I let them know that I’m here for them, if they need me. And occasionally, with very young children, once they’re regulated, I might ask questions that lead them to figure out that those feelings indeed pass, they don’t last forever, and that they will come through, no matter how they are feeling right now.

That’s it.

I don’t try to judge, fix or otherwise suggest any solutions. Because it makes the child feel like they are wrong to feel those feelings and we’d have lost an opportunity to build the foundations of emotional self-regulation.